Source: BBC News

John Dramani Mahama has been Ghana’s president once before – and now he is back for another punt at the top job.

The 65-year-old led Ghana from 2012 to 2017 and is one of the West African country’s most experienced politicians. He has served at all levels of office, as an MP, deputy minister, minister, vice-president and president.

Long before it became a career, politics played a significant role in Mahama’s childhood. When Mahama was just seven, his father, a government minister, was jailed during a military coup and later went into exile.

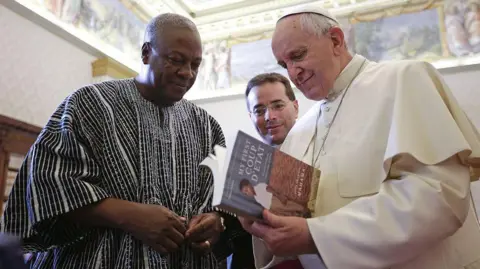

Personal trials like this appear in Mahama’s acclaimed writing – he has been published by a number of international news outlets and his memoir, My First Coup D’etat, won praise from two African literary greats, Ngugi wa Thiong’o and Chinua Achebe.

When penning his manifesto for this year’s elections, Mahama told voters Ghana “is headed in the wrong direction and needs to be rescued”.

But critics argue he may not be the right man for the job, given that his administration was hit by economic problems and a string of corruption scandals.

Mahama’s journey began in 1958, when he was born in the northern town of Damongo. After a few years he moved to the capital, Accra, to live with his father, Emmanuel Adama Mahama.

In My First Coup d’Etat, Mahama Jr describes himself as “an observant child with an active imagination and an unbounded curiosity”.

He was also relatively privileged. The family had another home in the town of Bole, which at the time was not on the national grid. Mahama’s parents were able to invest in a diesel generator for their six-bedroom house, meaning theirs was the only house in the town with lights.

Local residents would gather outside the house when night fell, captivated by the curious orange glow.

The future president attended Achimota boarding school, a prestigious institution known for educating heads of state like Ghana’s Jerry John Rawlings, Zimbabwe’s Robert Mugabe and Kwame Nkrumah, Ghana’s first prime minister after it gained independence from the UK.

It was at Achimota, in 1966, that Mahama heard there had been a coup. Military and police personnel had stormed Ghana’s government buildings, seizing power from Nkrumah, who was away on a foreign trip.

As updates trickled in, Mahama became increasingly anxious – he had heard no word from his father. Seven-year-old Mahama feared his father had been killed because of his proximity to Nkrumah.

It turned out his father had been imprisoned – he would remain in jail for approximately a year.

In 1981, after a second military coup, Mahama’s father fled the country for Nigeria.

Meanwhile, Mahama spent his twenties and thirties studying – he got a Communication Studies degree from the University of Ghana before studying at Moscow’s Institute of Social Sciences.

Mahama noted that his stay in Russia, then part of the Soviet Union, alerted him to “the imperfections of the socialist system”.

After returning to Ghana in 1996, Mahama followed his father’s footsteps into politics.

He was elected as a Member of Parliament for the National Democratic Congress (NDC) party and from there, scaled the political ranks. He zeroed in on the NDC’s messaging, taking up roles as the parliamentary spokesperson and minister for communication.

In 13 years, Mahama worked his way up to become vice-president, second-in-command under President John Atta Mills.

But after just three years in office, Mills died unexpectedly at the age of 68.

Just hours after this tragedy, a 58-year-old Mahama was sworn in as president. In his speech, Mahama described the day as the “saddest” in Ghana’s history.

General elections were held later that year and voters chose to keep Mahama in office.

So what kind of leader is Mahama? Franklin Cudjoe, a Ghanaian political commentator and head of the Imani Centre for Policy and Education, told the BBC the former president was an “excellent communicator”.

While political scientist Dr Clement Sefa-Nyarko described Mahama as a “pragmatist”.

Mahama has the it-factor but only in a climate where “politics is driven by reality and intelligent communication”, said Dr Sefa-Nyarko, who lectures on African leadership at King’s College London.

But in contemporary Ghana, many voters are captivated by overambitious pledges, according to Dr Clement Sefa-Nyarko, which means pragmatic Mahama is “not able to charm the populace much”.

When campaigning to stay in power ahead of the 2016 elections, Mahama highlighted various infrastructure projects completed under his administration, such as those in the transportation, health, and education sectors.

But under his watch, Ghanaians also experienced an ailing economy and widespread power cuts. Mahama was nicknamed “Mr Dumsor” in reference to the blackouts – “dum” means off and “sor” means on in the local Twi language.

His term was also blighted by corruption scandals. For instance, a UK court found that aviation giant Airbus had used bribes to secure contracts with Ghana for military planes between 2009 and 2015 – but Ghana’s Office of the Special Prosecutor concluded there was no evidence that Mahama was involved in any corrupt activities himself.

There are “lingering issues” surrounding these graft scandals – ones that the current electorate will “remember”, Mr Cudjoe said.

But he also points out that, according to Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI), corruption became worse under Nana Akufo-Addo, who beat Mahama in the 2016 elections.

Ghana averaged 45.8 under Mahama but dropped to 42 under Akufo-Addo in the CPI ranking where zero equates to “highly corrupt” and 100 is “very clean”.

Mahama attempted to win his old job back in 2020, but lost out to Akufo-Addo once again.

Despite these defeats, Mahama has remained in the political sphere – he is currently leader of the opposition.

He also enjoys a busy life away from politics – he has seven children and spends time with his wife, Lordina.

Mahama is also a prolific writer. Asides from his memoir, he has written for media outlets like The New York Times, leading African-American magazine Ebony and Ghana’s state-owned Daily Graphic.

Mahama has also expressed his passion for music, saying Nigerian Afrobeat icon Fela Kuti helped him form “political consciousness” and that Michael Jackson is “one of the greatest artistes that ever lived”.

And in a full-circle moment, the former president was immortalised in Mahama Paper, a song by Ghanaian dancehall star Shatta Wale. Wale said the title was a reference to the Ghanaian banknotes printed during Mahama’s administration.

Naturally, Mahama has used the hit in his current campaign, pointing out that under Akufo-Addo, Ghana has plummeted into its worst economic crisis in years.

He has also been reminding Ghanaians of his extensive political experience but the fact remains – he was voted out of power once before as the public felt his performance wasn’t good enough.

Mahama is seeking to persuade voters this time will be different – a communications whizz hoping his message is clear enough to win him a second chance in Ghana’s highest office.

By: Wedaeli Chibelushi